Supernatural Annunciations

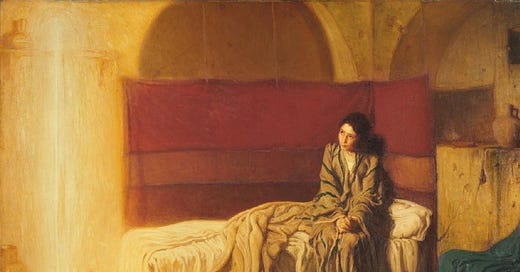

After 400 years of silence, with no dreams, no visions, no prophetic voices, what was the first clear sign that God was bringing his redemptive program to a climax?

Supernatural Announcements

The first thing that strikes the reader of the initial announcements regarding the coming of the Christ is their supernatural character, both in the means by which the message is delivered and in the content of the message itself. These initial annunciations come not by a prophet of the Lord, but by a messenger sent directly from heaven itself. Heaven-sent messengers appear to Zechariah the father of John the Baptist; to Mary the mother of Jesus, followed by an appearance to her husband, Joseph; and upon Jesus’ birth an innumerable company of angels to shepherds in Bethlehem’s fields (Luke 1:11–20, 26–38; Matt. 1:20–21; Luke 2:8–14). A special star in the heavens guides the magi to the Messiah, while the Holy Spirit provides special revelation to aged Simeon and Anna (Matt. 2:1–2, 9; Luke 2:25–27, 36–38). These extraordinary phenomena suit well the whole realm of supernatural activity that characterized God’s redemptive revelation from the time of the patriarchs. They manifest their significance even more dramatically against the stark backdrop of the four hundred years separating the age of the old covenant from the new. Yet a clear point of continuity is established by the fact that the heavenly messenger who first breaks the revelational silence by communicating with Zechariah the father of John the Baptist is none other than Gabriel, the same heavenly messenger who revealed mysteries to Daniel at the end of the old covenant era (Luke 1:19, 26; Dan. 8:16; 9:21). In addition, these supernatural announcements focus on significant supernatural events soon to take place. Elizabeth, well past the age of bearing children, will have a son (Luke 1:13). Her experience follows the pattern of divine interventions related to the bearing of a godly seed by barren women of the old covenant era (Gen. 11:30; 16:1; 18:11; 25:21; 29:31; Judg. 13:2). But even more significantly, Mary the virgin will conceive a son by the power of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:26–35). This special One to be born, unique in the history of humanity, is described by the messenger from heaven as “great” and “the Son of the Most High” (v. 32a). God will give him the “throne of his father David,” and he will “reign over the house of Jacob forever” (vv. 32b–33). By this announcement, he is clearly identified as the person destined to fulfill all the promises concerning a coming Messiah descended from David who will rule over the Israel of God.1 His supernatural birth from the virgin dramatically underscores his unique role as the only Son of God who is equal to the Father.

A Supernatural Sign

In recent days, even evangelical scholars have shown a willingness to concede that Isaiah’s prophecy spoke only of conception by a “young woman,” not a virgin. But a proper understanding of Isaiah’s prophecy hinges not only on the precise meaning of the word for “virgin” or “young woman,” but on the context as a whole. The intent of the Syro-Ephraimite coalition according to the prophet Isaiah is not simply to establish military superiority over the kingdom of Judah, but to terminate the Davidic line of royal succession that by now has continued for over 250 years (Isa. 7:6). When Isaiah offers doubting King Ahaz a sign of confirmation, he proposes the outer limits of the miraculous: “in the deepest depths or in the highest heights” (v. 11). The prophetic response to the king’s niggardly refusal must somehow come up to the prophet’s own proposed standards. What is God willing to do that will ensure the unbrokenness of his oath to David? What supernatural intervention will he initiate to counter this bold assault against his integrity as a covenant-keeping God? “Behold!” Be startled! Stand amazed!

So now is the prophet to declare the rather pedantic fact that a “young woman” will have a child? Would this commonplace event of an ordinary childbirth measure up to the expectations created by the historical circumstance as well as the prophetic offer of a supernatural sign in highest heaven or deepest earth? Hardly so. The measuring line of an event that may be categorized as “supernaturally spectacular” in Isaiah’s opinion may be found in the later incident involving Hezekiah’s illness. Isaiah promises he ailing king a “sign” that he will indeed be given an additional fifteen years. The sign is that the sundial will go backward ten steps (Isa. 38:8).

Try to imagine all the cosmic implications of a reversal of the movement of the sundial. The earth’s rotation suddenly stops, reverses, and starts again. But in the meantime, what happens to all the myriads of objects on the earth’s surface, not to speak of the oceans’ depths!

The birth of a child to a woman still in her state of virginity could serve as an appropriate “supernatural sign.” Such a miraculous birth could also provide an adequate response to the demands of the situation. God would be true to his covenantal oath to David. Nothing could interrupt the ongoing rule of a divine representative from the Davidic line as appointed by the Lord. If necessary, even a virgin would conceive and bear a son, and this special son would be designated as Immanu-El, God incarnate dwelling as sovereign ruler among his people.

The debate over Isaiah’s choice of the word almah over betulah has dragged out for many years.2 But no one has yet laid claim to Martin Luther’s offer of a hundred Gulden to anyone who could show that Isaiah’s chosen word (almah) ever referred to a married young woman.3 It may be acknowledged that the term betulah (the word that Isaiah chose not to use) more precisely speaks of a “virgin,” though it must also be recognized that the word may on occasion designate a married woman (Joel 1:8). But almah (Isaiah’s chosen word) always appears to mean “unmarried young woman,” thereby excluding the wife of Hezekiah or Isaiah from consideration. So should it be concluded that this “unmarried young woman” who will give birth to Immanu-El has lost her virtue? If she has not, which would seem much more likely, she must be viewed as a “virtuous unmarried young woman.” In any cultural context, a virtuous unmarried young woman is a “virgin.” So not without good reason did the Septuagint translators, three hundred years before Matthew wrote his Gospel, render this word with the unequivocal parthenos or “virgin.” So: Behold! Be amazed! A virgin will conceive and bear a son; and since his conception is uniquely by the power of the Holy Spirit, this child must be recognized as “son of God” in a truly unique sense. The annunciations rightly underscore the supernatural character of the revelations and the events that inaugurate the age of the new covenant. And should it have been otherwise? If nothing less than the sovereign, divine intervention of God himself was capable of accomplishing the work of restoring a fallen world, should not the initial beginnings of that wondrous work be clearly marked as divine in origin? Let those who wish for man to redeem himself go their own way in their own strength. Let them repeat he frustrating efforts of this Herculean task from now until the end of the age. But in the process, let them also take one more hard look at the witness of these annunciations. Are not the anticipations of the prophets being fulfilled? Were not these very events predicted several hundred years before their occurrence? Does not the record of the succeeding events of the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus confirm his uniqueness as the Messiah sent by God to bring to pass the promises of the prophets?

As has been stated in response to unbelief in the gospel testimony to the virgin birth:

The virgin birth is posted on guard at the door of the mystery of Christmas and none of us must think of hurrying past it. It stands on the threshold of the New Testament, blatantly supernatural, defying our rationalism, informing us that all that follows belongs to the same order as itself and that if we find it offensive there is no point in proceeding further.4

Supernatural Salvation

Though deliverance from social oppression by foreign powers would ultimately be included in the righteous reign established by Messiah, the initial “deliverance” finds its focus elsewhere. This virgin-born son is to be called “Jesus,” meaning “Yahveh saves,” for “he will save his people from their sins” (Matt. 1:21). The restoration of God’s people from their state of being under the heavy hand of God’s judgment must begin exactly where the prophets had indicated. Apart from the forgiveness of sins, there can be no salvation. Even residing in the land of promise does not automatically indicate restoration from being exiled outside of God’s presence. A genuine reconciliation to God must mark the beginning of the new life of the new age.5

Cf. Geerhardus Vos, Biblical Theology: Old and New Testaments (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1948), 306, who notes that in the annunciations there is “a perceptible intent to fit the new things into the organism of the Old Testament History of Redemption.”

Cf. H. G. M. Williamson, King, Messiah and Servant in the Book of Isaiah (Carlisle, UK: Paternoster Press, 1998), 103. Williamson agrees, “for the sake of the argument,” that the almah of Isaiah 7:14 “does not (in its original context, at least) refer to a technical virgin,” while at the same time insisting that it “cannot refer to a woman who has already borne a child some years before.” He proceeds to indicate his judgment that “it needs hardly to be said that in the immediate context the prediction of his birth is securely tied to the prevailing historical circumstances of the reign of Ahaz, so that a long-range messianic prediction is ruled out, at least at the primary level” (108–9). Cf. Daniel Schibler, “Messianism and Messianic Prophecy in Isaiah 1–12 and 28–33,” in The Lord’s Anointed: Interpretation of Old testament Messianic Texts, ed. Philip E. Satterthwaite, Richard S. Hess, and Gordon J. Wenham (Carlisle, UK: Paternoster Press, 1995), 99. Schibler concludes that the term almah “refers to someone in the entourage of Ahaz,” and that the name “Immanuel” indicates that “for Isaiah, Hezekiah’s birth heralds the presence of God among the faithful in Jerusalem in a most precarious situation.” Cf. J. Gordon McConville, “Messianic Interpretation of the Old Testament in Modern Context,” in The Lord’s Anointed: Interpretation of Old Testament Messianic Texts, ed. Philip E. Satterthwaite, Richard S. Hess, and Gordon J. Wenham (Carlisle, UK: Paternoster Press, 1995), 14, who notes that Isaiah 7:14 “appears to have its fulfilment in the immediate context of Ahaz’ reign.” The implication of the change of the heading over Matthew 1:18 in the 2011 version of the NIV is not clear. It simply reads, “Joseph Accepts Jesus as His Son,” which is a rather bland heading over a section of Scripture that proclaims one of the most astounding events in the history of humanity—the virgin birth, the incarnation of the eternal Son of God, the second person of the Trinity.

Cf. Edward J. Young, the Book of Isaiah, vol. 1, chapters I–XVIII(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), 287n35, referring to the comments of Vischer. Vischer notes that in characteristic fashion, Luther added that the Lord alone knew where he would get the hundred Gulden. But as history has proved, Luther had no need to worry.

Donald Macleod, The Person of Christ, Contours of Christian Theology (Downers Grove, L: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 37.

Cf. N. T. Wright, Christian Origins and the Question of God, vol. 1, The New Testament and the People of God (London: SPCK, 1992), 268–72; 299–307; vol. 2, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 126–29; 268–74. Wright more than any other contemporary scholar develops the idea of Israel’s hope in terms of restoration from exile. This restoration in particular must involve the forgiveness of sins. Says Wright: “Forgiveness of sins is another way of saying ‘return from exile.’” Victory, 268 (emphasis original). For further analysis of Wright’s focus on “return from exile,” see the section “Death of Jesus” in chapter 6.

This excerpt is taken from O. Palmer Robertson, Christ of the Consummation. A New Testament Biblical Theology. Volume 1: The Testimony of the Four Gospels (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing Company, 2022), 21-25